The Big Short, Our Brand Is Crisis and the mistake in talking down to audiences

The following piece discusses The Big Short and Our Brand Is Crisis in detail, including references to the films’ final moments. Both films are based on real life events and in both cases it is relatively easy to see the direction in which they are going. But if you would rather not risk any spoilers then bookmark this page and come back once you’ve seen the films.

The following piece discusses The Big Short and Our Brand Is Crisis in detail, including references to the films’ final moments. Both films are based on real life events and in both cases it is relatively easy to see the direction in which they are going. But if you would rather not risk any spoilers then bookmark this page and come back once you’ve seen the films.

The Big Short and Our Brand Is Crisis finally arrive in UK cinemas this week and both hinge on a rather cynical final act twist and a similar approach to imparting important information. An approach that again reeks of cynicism. But this is not a cynicism about each of the films’ subjects – the banking crisis and America’s influence on foreign countries – but instead a attitude towards the audiences for the films that borders on contempt.

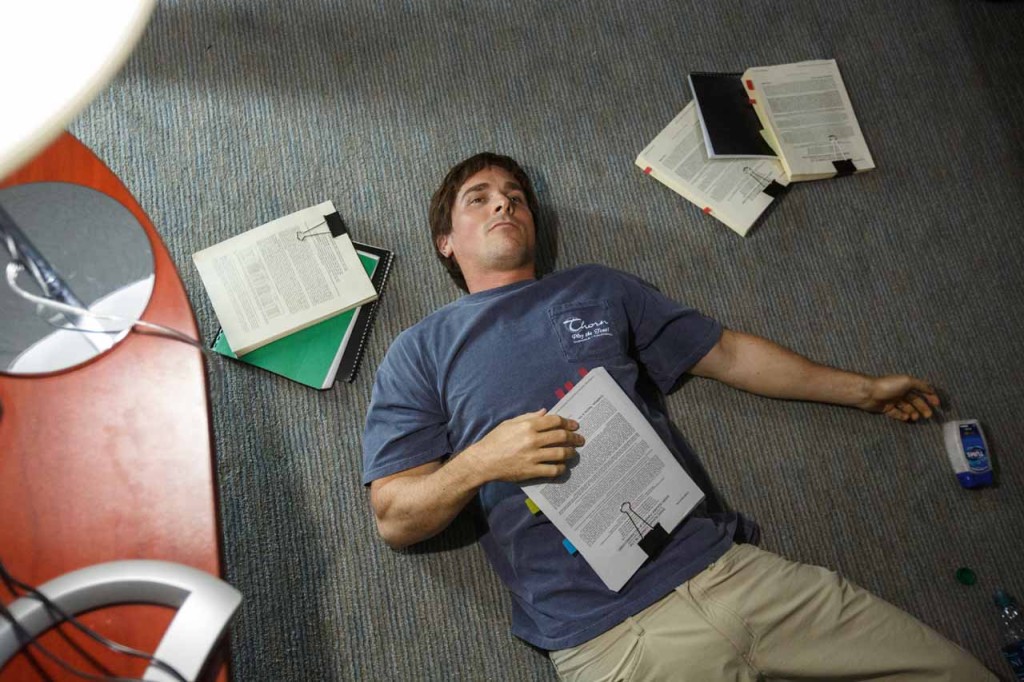

The Big Short is, in some ways, Adam McKay‘s first foray into serious drama, but whilst his intent may very well be serious, his execution most certainly isn’t. McKay and co. take a rather scattershot approach to the subject of the housing bubble collapse of a decade ago, pulling in various characters and stories and attempting to pull all of these pieces together to make a satisfying whole. Unfortunately this never happens and the film frequently resembles the messy pile of Jenga pieces that trader Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) is left with following a particularly silly attempt at crafting a fun analogy for the housing crisis.

This is one of many attempts by McKay and co-writer Charles Randolph – who adapted Michael Lewis‘ book of the same name from 2010 – to explain to the audience the rather unsexy world of banking and subprime mortgages in a way that they might understand and hopefully won’t bore them.

The assumption being that you, the audience, don’t understand any of this stuff. And even if someone tried to explain it to you in the dumbest way possible you’d still probably mentally switch off and/or start playing with your phone. So, instead we get fourth wall breaking cameos from Margot Robbie, Selena Gomez and Anthony Bourdain to help explain things simply, whilst at the same time ensuring our attention is held. Because, y’know, they’re celebs.

The assumption is that in order to take our medicine, we need not just a spoonful of sugar, but enough corn syrup to drown an elephant in.

The makers of Our Brand Is Crisis may not be quite as egregious in their distrust of an audience’s ability to pay attention to serious topics and be trusted with understanding complex information, but for a film that is very much about politics, Our Brand Is Crisis again plays very much like a screwball stoner comedy.

Now there is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with this – as there isn’t in taking a humorous approach to the banking crisis – but the execution again very rarely trusts the audience’s intelligence and instead relies on their perceived naivety and possibly even stupidity.

The film begins with rather awkwardly and unconvincingly shot footage of Sandra Bullock‘s character, political consultant Jane, being interviewed about her career. She has been involved in a number of high profile political campaigns and the bulk of the film takes place during one such campaign, a presidential race in Bolivia.

Cue a sequence on the plane to Bolivia in which another character unloads a significant information dump about the country. Including multiple mentions of the altitude of where they are going. A somewhat inconsequential fact one would think, until it becomes clear that this is going to be mined for a significant amount of ‘humour’ regarding Jane’s inability to cope with the altitude.

Any time the film gets particularly serious in the first act or has relied heavily on scenes in which characters are talking about politics, director David Gordon Green cuts to Jane throwing up, groaning or shovelling crisps into her mouth. Here the sugar is broad comedy. And it’s equally as misguided and almost as insulting as in The Big Short.

In one particularly misjudged sequence Jane and her team are travelling between villages and decide to try and beat the bus of another candidate, who is doing the same thing. It all gets a bit Wacky Racers for around ten minutes and climaxes with Jane mooning out of the window at the other bus.

David Gordon Green seems to be taking more of a cue from his previous work like Your Highness or The Sitter here than he is from anything like George Washington or Joe. Again, it’s worth mentioning that there’s actually something to be said for adding humour to an otherwise serious subject, but Our Brand Is Crisis and The Big Short don’t tackle serious subjects with a humorous approach, instead they fail to take these subjects seriously, negating any of the importance these films could have had. They are like blueprints for complex structures that have been drawn using chunky crayons.

Both also rely on a narrative structure that assumes the audience are simply too clueless to second guess it and perhaps even too ignorant to understand the ‘reality’ of the situation. Our Brand Is Crisis attempts to get the audience invested in the struggle to make Castillo president, even though he’s obviously not the best person for the job, and The Big Short plays the same trick by trying to convince us that the guys betting against the big banks are heroes of a sort that we should be punching the air for. Despite the fact that these guys obviously helped cause the crash. Something that will be obvious to anyone that thinks about even just the premise for a moment or two.

That these guys aren’t perfect heroes and Castillo isn’t Bolivia’s saviour, but its worst enemy, isn’t a problem, but again McKay and Gordon Green underestimate their audiences by assuming that they can play a narrative game that will pull the rug out from under us and ‘make us think’. But neither film is even close to being smartly written enough to pull that off and in attempting it and failing both come across simply as even more patronising.

Our Brand is Crisis and The Big Short are both films that assume very little of their audiences and substitute genuine insight for simplistic finger pointing and daft attempts at comedy. These subjects and the audiences for these films deserve a lot better.