The catch-all crazy characterisation, victim blaming shame and cheap thrills of Gone Girl

This article contains spoilers for Gone Girl and a discussion of the second half of the film. Read on only if you are happy to be ‘spoiled.’ We would typically hold this kind of article back until some days after the film’s release, but in this case there’s already a published document that spoils everything: the original book.

This article contains spoilers for Gone Girl and a discussion of the second half of the film. Read on only if you are happy to be ‘spoiled.’ We would typically hold this kind of article back until some days after the film’s release, but in this case there’s already a published document that spoils everything: the original book.

The literal translation of Män som hatar kvinnor, the original novel on which director David Fincher based his 2011 film The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, is Men Who Hate Women. Both novel and film was very much focused on the despicable acts that some men do to women, and on the implications of those actions. Now Fincher’s latest film, Gone Girl, engages just as much with misogyny, but with less clarity of thought and meaning.

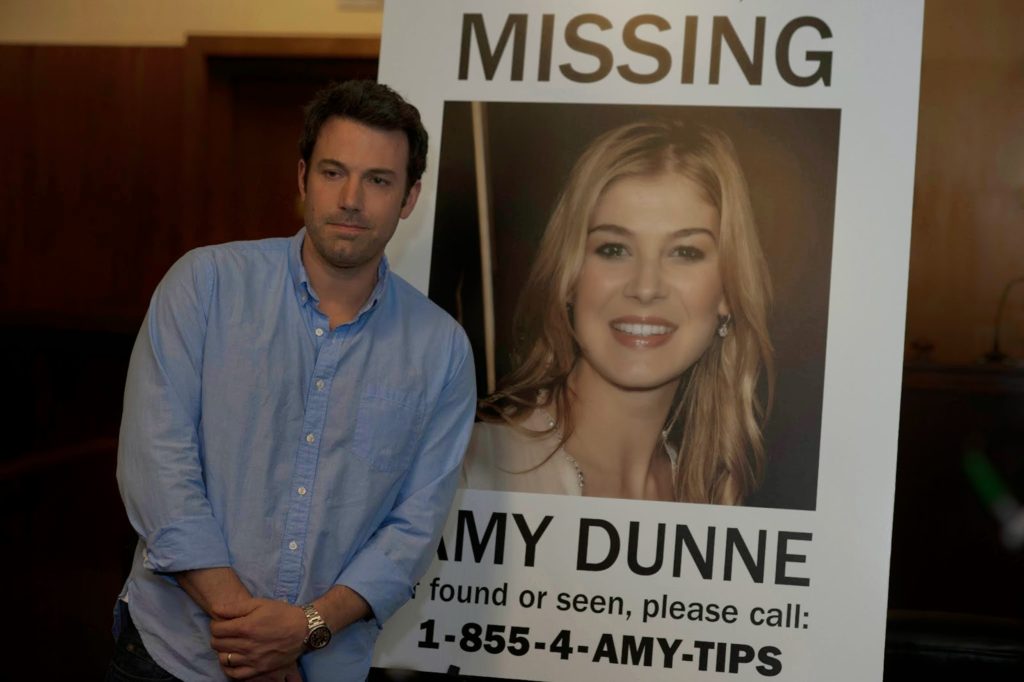

Gone Girl begins with the introduction of Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), the schlubby husband of Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike). Nick might be taken for a hulking, useless lump of a man who appears detached from his richer, more cultured and seemingly picture perfect wife. To further enforce a distinction in perception between the couple, it’s revealed that Amy is known internationally as ‘Amazing Amy’, thanks to a series of fictionalised, illustrated books that her parents had loosely based upon her life.

It’s a little unclear, because Nick is so emotionally distant in the film’s first hour, but the intention appears to be for us to feel sorry for him. With Amy absent for the first hour and no other prominent character stepping forward, Nick is, almost by default, the protagonist. He becomes driving force for the narrative as we see it as he searches for his wife, and the other characters are merely satellites orbiting his central story.

But then there are the twists.

There is the growing suspicion in the town and even amongst Nick’s own family – specifically, his twin sister with whom he co-owns a local bar – that he may have actually murdered his wife. There’s little sense that the audience are expected to believe this, and it seems clear from the opening scenes of Nick happening upon a smashed coffee table and his wife missing, where he is alone and so has no reason to pretend, that he didn’t ‘do it.’ Still, a a lot of mud is thrown at Nick, some of it being real dirt on him and his past, and every now and again, a bit sticks.

Lending a hand with the mudslinging are a busybody neighbour, Noelle Hawthorne (Casey Wilson); two cable TV hosts; Amy’s mother; and even to some degree the sympathetic cop investigating the disappearance, Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens). Nick is also ‘tricked’ into having a smiling selfie taken with a volunteer who flirts with him at a meeting of volunteers helping to search for Amy.

What do all of these characters have in common? Every single one of them is female. All of them, without an exception.

The only named men we meet outside of Nick are the comically dopey assistant to Rhonda, who is admittedly very critical of Nick; Amy’s father, who is little more than walking furniture; Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris), another victim of Amy’s plan, and Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry), an attorney who helps Nick in the second half of the film.

That Nick is facing so much opposition from females leads him to comment on how he wishes he’d stop getting picked on by “all these fucking women.”

Nick is being hounded by the press and he’s a nationally despised figure and who does he blame? Women. But Nick is essentially the film’s hero and victim. Without any clear idea of what has happened to Amy until the film’s big reveal, the audience are being encouraged to sympathise with a man who at least feels a great deal of animosity towards women even if he doesn’t hate them entirely.

And perhaps surprisingly, the reveal that Amy is alive further encourages us to sympathise with Nick as it’s now confirmed he’s not the man that everyone suspects him of being.

Amy is alive and was behind her own disappearance, a plan she carefully orchestrated over several months to frame Nick, destroy him in public and ultimately lead to him receiving the death penalty for her ‘murder.’ Amy reveals this twist through voiceover, as the film switches to her point-of-view on the day of the disappearance and we see her driving away and embracing her new found freedom.

It’s in this sequence that Amy delivers her cringeworthy deconstruction of men’s desire for a ‘cool girl.’ It’s awkward because Pike and Affleck are, respectively, in their 30s and 40s and the speech is juvenile.

Amy sees other women driving past in cars and assigns types to them on the basis of one or two simplistic signifiers. This monologue has been praised, by fans of both the novel and of the film, as a feminist call-to-arms, a break from what women are expected to say and do. But does it not also work as a more sophisticated extension of slut-shaming?

This sequence doesn’t actually deliver any commentary on the subjugation of women through these predetermined roles and ‘types’ but instead pits women against women, or at least one woman against other women. Amy definitely holds Nick accountable but she’s also laying blame at the feet of other women.

After Amy runs away her hideout is in a trailer park of sorts, and it’s definitely step down from her seemingly idyllic Stepford house. While she’s here she seems energised and, if still rather angry, also liberated and happy. She befriends another woman, Greta (Lola Kirke), and while Amy plays nice it’s apparent that she looks down on Greta. In one scene played for laughs, Amy spikes Greta’s drink with spit.

When Greta and her boyfriend turn up to rob her, Amy asks Greta how her boyfriend managed to talk her into this and Greta replies that it was her who has convinced him. Gone Girl is filled with female characters who get things to do, but so many of these things are actually negative.

The ‘cool girls’ monologue is something that Amy uses to explain her anger at Nick for his infidelity. As we learn, Nick cheated on Amy with a twenty-year-old named Andie (Emily Ratajkowski).

Ratajkowski is most famous, unfortunately, as a dancer in the video for Robin Thicke‘s misogynist pop calamity, Blurred Lines. Are we supposed to find her casting here funny in a meta-textual kind of way? More likely, it seems, she’s being used in a very similar way here as in the music video, with Gone Girl providing almost no inner life or character development for Andie, but an opportunity to shed some clothes and engage in erotic pantomime. It’s arguable that Ratajkowski’s primary function in this film is to titillate.

But she does provoke an important plot twist when, eventually, Andie announces the secret affair in a press conference, a direct counterpoint to her telling Nick that she loves him and won’t reveal their affair. This threatens to wreck Nick’s ongoing attempts to improve his public image and trips up his plan to admit the affair on television himself. At this point in the narrative Nick has been positioned as sympathetic tragic hero only to be betrayed and attacked by another woman.

That Nick cheated on his wife has been deliberately pushed into the background and the audience are being guided towards rooting for Nick in his battle of wills with Amy.

Nick’s time working for a men’s magazine and his affair with a student suggest that he’s not exactly an enlightened feminist, but the story we’re told seems to be designed to offset his attitude, even justify it. The characters in Gone Girl behave in ways that would recognisable from the demented ramblings of Elliot Rodger, Men’s Rights Activists, or the internet trolls fuelling ‘Gamer Gate.’ In fact, Amy even criticises Nick at one point for lounging about the house playing video games.

Sadly, the film doesn’t engage with or deconstruct these ideas; it’s barely even a pulpy riff on the subject. Gone Girl is far more facile than this volume of discussion would probably suggest.

Unfortunately, the worst is yet to come. It seems that Amy has a favourite form of punishment for the men that cross her or stand in her way, and these scenes play out like a gift to the MRA ‘campaigners’ and their ilk. Not only once but twice, Amy seems to be using an accusation of rape as a weapon against men There’s also the possibility, seeing as Amy is an unreliable narrator, that her reference to Nick physically assaulting her was nothing more than a fabrication.

Sexual and physical assaults against women are horribly common and the way in which the media reacts to them is often deeply harmful, to the point that widespread cynicism and a default mistrust have prohibited women from speaking out about their experiences. The idea that women frequently lie about being raped has been very successfully proliferated, and you’ll see evidence of how generally accepted the notion is from almost any online news story about a female victim of rape and the accompanying string of comments from readers that blame the victim and even allege her story is a lie.

But Gone Girl is cinematic fantasy, of course. A fictional film featuring an incredibly exaggerated female character. Of course it is, and I would forever defend the rights of filmmakers to tell any story they want.

But I may not be so quick to defend what these filmmakers may be saying.

It’s very relevant to the subject matter of Gone Girl that the filmmakers consider cultural attitudes towards the victims of rape, and the popular misconception that women frequently lie about having been raped.

I’m not arguing that Fincher and Gone Girl novelist and screenwriter Gillian Flynn shouldn’t have represented a woman who pretends to be raped, but there are meanings in their work that was created by this choice. It’s also of note that there’s no explanation for Amy’s actions beyond the excuse that she’s catch-all ‘crazy.’

Many critics have praised Gone Girl for it’s trashiness, celebrating the fact that the film is schlocky and that Fincher’s artistry as a filmmaker – something I’m actually not entirely convinced of, myself – somehow elevates the material. But there seems to be little discussion of which elements actually constitute this trashiness, and what these elements actually mean.

I agree that Gone Girl is trashy. Its commuter-novel, airport-paperback roots are very evident and so to is its superficiality. Some have suggested that this is a sharp satire of a modern American marriage and whilst I’d believe that everyone involved was aiming for this, what we have has eventually ended up being about as sharp as a marshmallow.

The areas of gender politics into which Gone Girl moves are filled with difficult subjects and serious issues worthy of very serious consideration and treatment. Here, though, they’ve been used for would-be shocking reveals and surprise plot twists, designed to keep the ‘pages turning’ and the audience guessing. In a way, Gone Girl works in this respect, but only when its forward momentum distracts from the various events and representations that make up the story.

Around the ninety minute mark of Gone Girl I was unsettled enough that I wanted to leave. I stayed seated, however, hopeful that the film would say something about the many issues it was evoking, rather than just exploit them for cheap thrills. But it didn’t, and even now that “all these fucking women” line still sits in the forefront of my mind whenever I think about the film.

Gone Girl is on release now across the US and UK.