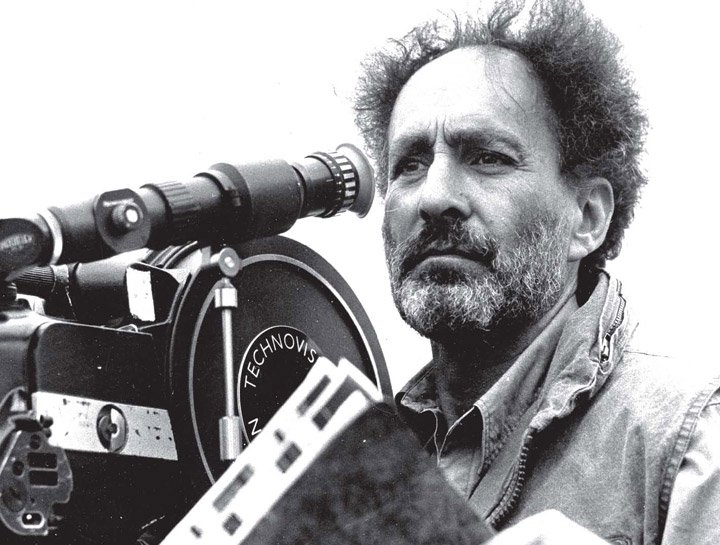

Monte Hellman Interview

At the time the casting of Two-Lane Blacktop was somewhat unconvential. Could you talk a little about how you came to choose the particular actors you used, specifically James Taylor and Laurie Bird.

Well, I think that James was probably the first one to be cast and I had been intervieweing just about every young actor in Hollywood and I didn’t find anyone that really struck me. I saw James’ photo on a billboard on the Sunset Strip and I was interested in his face and I asked our casting director Fred Roos if it would be possible to meet with him. He came in and that was it. I was convinced but we actually had to convince the studio at the time, which was not the studio that ultimately made the movie, and so we shot a screen test and everybody was thrilled with that and he was cast.

And then Laurie Bird was someone I had met when I went to New York and met with Rudy Wurlitzer and we were struck by some qualities that she had as a person that we thought were simiilar to the character that we were developing in the script. And so we spent two or three hours doing an audio interview with her and that was the basis for a lot of what went into the script for the character. Later on when I couldn’t find anyone to play the part someone had the bright idea to consider the girl that was the prototype, and that’s what happened.

Their screen tests are on the new Blu-ray and they’re quite intriguing to watch. Were they shot mostly just for the studio?

Yes, they were shot for the purpose of convincing the studio.

In Road to Nowhere the fictional director comments that casting is 90% of directing. Is that something you believe in?

Yeah, I would probably make it 95. [Laughs]

I think it’s something that I actually teach my students. I was looking at some scenes from students yesterday and somebody had a very successful scene because of the fact that they had found just the right actor. Also, it’s something I use to include not just the actors but the locations, they’re are part of the casting process.

You’ve had many strong female leads in your films, including Millie Perkins in your westerns and Cockfighter and Jenny Agutter in China 9, Liberty 37. How did you come to work with those actresses?

Millie Perkins was my next door neighbour and Jenny Agutter, I’m not quite sure how we came to her but when you go through a casting process on a picture that’s ready to be made you sometimes don’t have quite as much time as if you have a few more months to plan. People start throwing out ideas and one of them clicks and that’s what happens. You wind up with that terrific actor.

China 9, Liberty 37 to me feels more romantic than your other films. Is that something you would agree with?

Yes, I think it is more romantic than some of my other movies but I think that I tend to have a romantic outlook. I tend to like romantic movies. I think that may be more overtly romantic but I think some of the others are too, I think Two-Lane Blacktop is very romantic too.

I think so too but where specifically do you see the romance in Two-Lane Blacktop?

For me Two-Lane Blacktop was my way to do a version of Shoot the Piano Player and it’s really a story about a character whose tragic flaw is the inability to communicate and it’s all about his inability to communicate his romantic feelings that I think leads to his disappointment in the movie.

Do you yourself see the ending as a downbeat ending?

No, I think the ending is a way to stop the movie as opposed to a way to end it because unless you end with marriage or death [chuckles] there are no other endings in movies. So we just stooped the movie, we don’t end it.

I’m a big fan of the two movies you made in the Phillipines. There are a couple of lines in them that I particularly like, “Death is a punctuation” in Flight to Fury and there’s one in Back Door to Hell about how we’re all going to “die anyway, today, tomorrow, thirty years from now”.

[Laughs] I didn’t write either of those so I guess they’re the sentiments of Jack Nicholson and John Hackett.

Is that something that you liked about the scripts though. There’s a sense of fatalism to them, is that something that appealed?

I enjoy, y’know, a slight diversion towards philosophical discussion just as I do in life but I don’t really concentrate on that in my movies. It’s just part of the characters.

I think there’s a real end of era feeling to Two-Lane Blacktop. Do you feel that about it and did you get that sense at the time at all?

When you’re in any given time frame I don’t think we think ‘oh, this is 1989 the end of decade’, it’s just another year and more accurately it’s just another day, that’s all.

Do you see it looking back though?

I don’t really. I mean it’s easy to say that the sixties had a certain personality or something. I think there’s a certain truth to it though, London in the sixties was, using a term we would use in my classes in Stanford, a dynamic place to be at that time. And at other times Los Angeles has been the most dynamic place, at least in America, perhaps in the world. Things happen faster in certain places and at certain times but to say, okay this is a ten year period that happens to match the passing of a decade is possibly stretching it.

In a more general sense I suppose I’m getting at, was there a sense of a change coming or change happening?

Again something you’re not aware of at the time but looking back I would say that the time we made Two Lane Blacktop was certainly a stimulating time to be making movies, at least in Hollywood. We may never have that much freedom to make such unusual movies as we did at that time.

I spoke recently with Douglas Trumbull and he echoed those sentiments but also talked about recent changes in technology. I understand that’s something that you’re also interested in. Road to Nowhere was shot on Canon 5Ds, for instance. Do you find digital filmmaking liberating?

I’m an early adopter and I took to digital still photography very early on. I was appreciative of not having to breathe all those chemicals in the dark-room and I also appreciated the greater control you have, it’s much easier to manipulate the image than to have to kind of wave your hand in a funny way [laughs]. I like it a lot and I feel the same way about digital movies, it’s much greater control, you have greater control over the colour, it’s a more permanent control. In the lab you may have one batch that comes out good and then the next batch might be a slightly different part of the process in terms of the first film that goes through a new batch of chemicals being different from the last batch that went through before they changed the chemicals. There are so many variables in that system and it’s much more specific in the digital world.

I did used to love the dark-room though for the tactile nature of it though, is there anything about that which you miss?

I don’t miss that but I do miss handling the film. I used to work with an upright moviola and I do miss that, that was a very tactile experience and a much more physically active than just pushing buttons on a computer.

You’ve obviously had a lot of work as an editor on your own projects and other peoples. Is there one part that you prefer, the editing, the directing or the writing?

Having come originally from the theatre where part of the director’s job is not only coaxing a performance out of the players but also controlling the timing and so on, that’s two things and the editing is the equivalent of the second part, so I consider it a continuation of the directing.

Some directors and editors often say that the film is really made in the editing room. Do you feel that that’s the case or that a lot of it is on the page?

There’s no easy answer to that. Yes, there are some films that you’ve edited in your head and they just go together and other films become completely different in the process. I would say that Road to Nowhere was film that was drastically altered in the editing process.

Do you tend to storyboard beforehand?

I only storyboard when I’m forced to, which is when I’m doing special effects. So when I was doing all the miniatures for Avalanche Express, all the avalanche itself and the minature trains and so forth, that all needed to be storyboarded but if I don’t need to do it I don’t do it.

You made a diagram for Two-Lane Blacktop to proof a point too, is that correct?

Yeah, I did an overhead view looking down on the car and showing all the different positions the camera could have. It would give us that many perspectives and I used that when I went to MGM to try to convince them to finance the movie.

Do you still have the diagram?

No, I don’t. I wish I did [laughs].

Me too, I’d love to see it as I’m sure a lot of film fans would. You shot second unit on a few films too including Robocop. Did you need to do storyboards for that?

I didn’t do storyboards but Paul Verhoeven did storyboards. He didn’t like the idea of having a second unit director, I must say I don’t either if it happens to me, so he wanted to maintain his control over it as much as he could so he would give me storyboards everyday to dictate how I would shoot the scenes.

I’ve read that you shot second unit on The Big Red One too, is that true?

No, that’s one of those strange IMDB fantasies I guess, they have me down for a number of things that I had nothing to do with.

As a teacher is there one thing that you think is most important to teach your students or is there one thing that you think that you’re imparting to them that is the most use?

I basically, as much as I can, teach philosophy of filmmaking as much as any of the technique. I do a little bit of each. The rules, the grammar of filmmaking are so simple that you can teach them in about twenty minutes but it takes a lot longer to learn so sometimes we have to reinforce those lessons over and over again to get them across. It’s pretty simple stuff. I teach a basic philosophy though that’s based on a kind of mentor of mine, not someone I actually met but someone whose books I read, and that’s Artur Hopkins. It’s really again quite simple stuff, that we are at the service of the material that we are doing and that the job of the director is primarily to convince everyone of that. To make everyone part of this team working together and not to try and call attention to ourselves individually. It’s a little bit about being selfless and essentially the idea that anything that calls attention to a person or a technique is detrimental. That if you notice the music or if you notice the cinematography or if you notice the direction then you can be sure that it’s bad.

How do you feel generally about ‘breaking the forth wall’, so to speak, because in Road to Nowhere there’s an interesting game played with that?

Well it’s against everything I was ever taught, against everything I believe and what was amazing to me was how quickly the audience begins to believe again. We shake them up and knock them out of the movie and they come back within seconds and I think it has to do with our wanting to believe, when we go into that theatre, into that dark room, we want to suspend our disbelief and we want to be wrapped up in this story that we’re asked to participate in. It’s so powerful and I think that’s one of the big revelations for me and I think seeing how quickly the audience came back.

Just to return briefly to Two-Lane Blacktop, I understand there were scenes that were cut that no longer exist. Could you talk a little about these?

Well, the script turned out to be a very long screenplay. We shot most of it and we wound up with a three and a half hour first cut and we were contractually obligated to deliver a movie under two hours. We wound up with a movie that was actually an hour and three quarters. So we threw away half the movie [laughs] and yes there were some wonderful scenes. There was one scene in particular where they’re evading a cop car that’s trying to catch them and they pull into a residential neighbourhood and pull into the driveway and the cop car never shows up. They get out of their car and they look through the window at this house and they see a family of a man and a woman and their two children having dinner. There’s nothing said but there’s a kind of nostalgia about their sense of what they’ve left behind and the life they’re living now.

Is there any sense do you think that they want to recapture that kind of a family unit?

I don’t know, whenever you move on to another stage of your life there’s always a possibility that you’ll feel nostalgia for what you’ve left behind but at the same time that doesn’t mean that you’d necessarily like to go back to it.

The road as well is a powerful symbol of abandoning something, a lot of films have used it as symbol in this way. Do you see the road as having a potential for giving up on a a past life? What do you see as the symbolic potential of the road?

I think the road is what you perceive it is or what you wish it to be. It can be many things. To me the road is really a way to ground a movie in real life. One of my other mentors was Siegfried Kracauer who wrote a book called ‘Theory of Film’ in which he basically says that if you shoot a movie in a room without windows then it’s not really a movie because it doesn’t have any connection to the street or to life itself. But if you have a window and you see out into the world… and one of the trademarks of Darryl Zanuck is that he would have just that, he would have a window or an open doorway in every scene in his movies, even though he wasn’t the director, and there would be all this teeming life going on outside in the world and that made it a much more powerful movie.

In Road to Nowhere Mitchell Haven sees the world through the prism of films, his window into the world seems to be through film, Lady Eve and The Seventh Seal for instance. That seems to shape how he perceives the world. As something of a cine-nut myself I could empathise with that. Do you see the world through films, do they open your mind in that way?

I don’t know if I see the world through films but I think in Road to Nowhere he uses film as a way to connect to his love. He wants her to experience the emotions that he felt with these movies and in that way bond more closely with her. I think that he equally sees film through the real world, in other words he tries to represent reality with his cinema and that’s his attraction to a real life crime story that he becomes so in love.

I really enjoyed Road to Nowhere and am so happy to see you making films again. Is there anything next on the horizon?

We’ve got three projects now, two that Steve Gaydos has, one is a script that he’s already written called Rattlesnake Shakedown and another is a book that he’s just optioned by Herbert Gold called The Man Who Was Not With It and there’s a third project that I’ve had for a number of years called Love or Die which may be my next one. Whichever one comes together faster is the one that we’ll do, the one that we raise the money for.